That morning, I rose early and arrived at school just before seven. In the autumn and winter of eastern Taiwan, the renowned Taitung blue was nowhere to be seen, replaced by an endless expanse of clouds stretching beyond the horizon. My classmates and I stretched on the red earth track, our bodies still heavy with sleep, while my heart pounded, thump, thump, thump, against my chest.

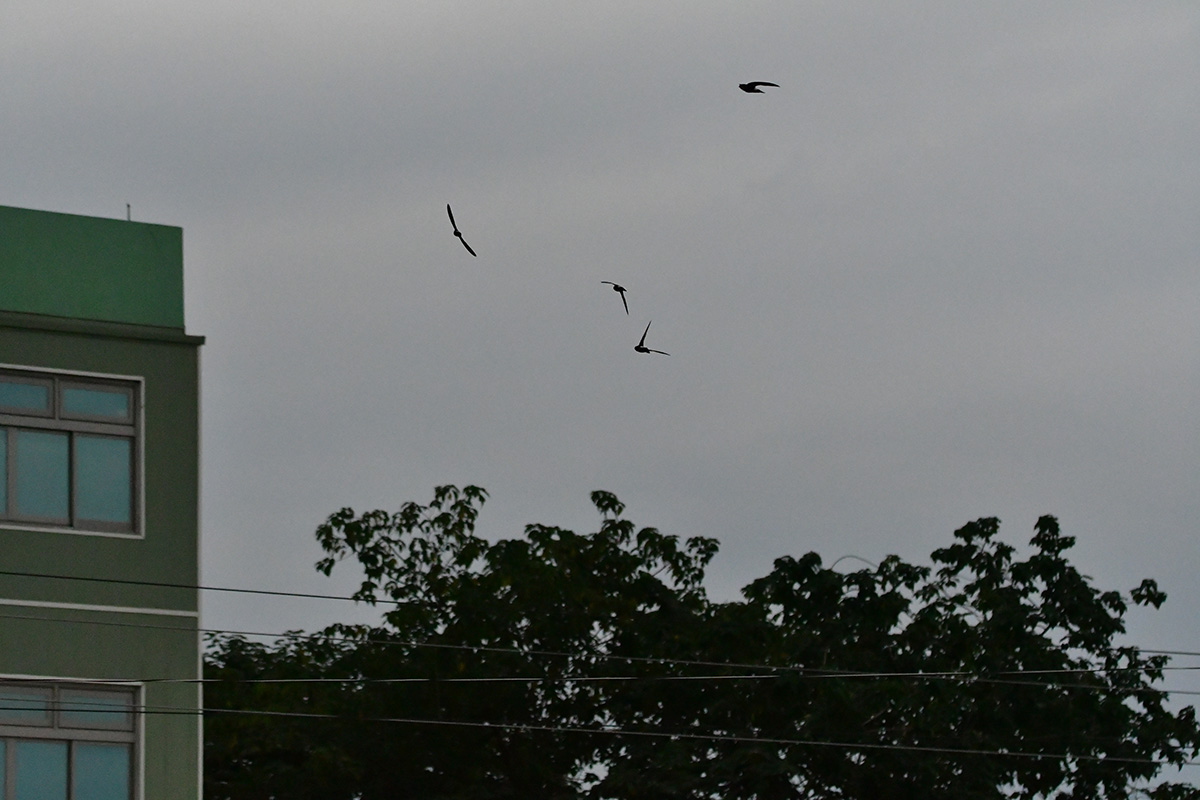

High in the distant sky, a few tiny black specks hovered, their high-pitched, piercing cries falling like icy needles formed from ice crystals—plummeting, quivering, and scattering before reaching the earth.

Everyone had long grown used to my habit of gazing at the sky. As my eyes lingered on the birds above, they casually reminded me it was time to step onto the track and practice passing the relay baton.

High in the distant sky, a few tiny black specks cast down sharp, thin cries from above. (Photo by Sun Wen-Hsiang)

During after-school practice, I once again heard the sound of icy needles shattering, this time much closer. Looking up, I saw a flock of House Swifts (Apus nipalensis) overhead, their sleek, sickle-shaped wings drawing virtual paths across the late autumn dusk.

House Swifts are a familiar sight in the urban areas of Taitung, where I grew up. During the rush hours of morning and evening, as you pass by bridges or tall buildings, their high-pitched, trembling calls can easily be heard above the din of traffic. During those hours, the swifts are mostly gliding effortlessly on air currents high above.

Structurally, the wing bones of House Swifts are shorter than those of most birds, while their outer primaries are nearly as long as their bodies. When they fly, they move like sickles—precise, sharp, and so lightweight that they effortlessly ride the air. Sometimes, they ascend higher and higher, like flocks of Chinese Sparrowhawks (Accipiter soloensis) waiting for thermal currents, eventually vanishing into the sky.

Such flights are referred to in English as "vespersflights" or "vesper flights," meaning "evening prayer flights."

When they fly, they move like sickles—precise, sharp, and so lightweight that they effortlessly ride the air.

In Vesper Flights, Helen Macdonald notes that ecologist Adriaan Dokter used Doppler weather radar to study the flight of swifts. He suggests that swifts may ascend to gather atmospheric information and predict weather conditions:

"Evening flights take swifts to the top of the convective boundary layer (CBL), the atmospheric layer … where they spend most of their time. By reaching the top, swifts encounter air currents shaped by large-scale weather systems rather than the terrain below. At these heights, they can not only observe frontal cloud systems illuminated by distant twilight but also use the winds to assess the movements of these systems.

Helen, on the other hand, writes in a more poetic manner. She describes what the swifts do as: "Fly to transcendent heights to clearly discern their position."

Most of a House Swift's life is spent in the sky, where they chase, forage, court, and mate, almost blending into the wind. Their legs are short and weak, shaped like hooks, and incapable of supporting their body weight upright. They can only cling to rock faces and cement protrusions. To take flight, they must first jump downward. If they accidentally land and perch, they must expend extra energy climbing to a higher point before they can fly again.

House Swift's legs are short and weak, shaped like hooks, and incapable of supporting their body weight upright. They can only cling to rock faces and cement protrusions.

Two years ago, one day after school, I passed by the Taitung County Gymnasium, which was shrouded in scaffolding and plastic safety nets. House swifts had been nesting on the building's exterior, but during construction, their chicks were relocated to artificial boxes unsuitable for their natural behavior. Although the chicks were urgently transferred to WildOne Wildlife Hospital after the relocation was deemed inappropriate, many still did not survive.

I gazed from afar at the adult house swifts still circling the gymnasium. They flew around the safety net, some managing to find gaps, but even after squeezing through, it was all in vain. Their young would not be returning. The swifts' urgent calls and rapid flight wove a gloomy net, enveloping the entire sky of the breeding season.

So far, we have only confirmed certain behaviors in birds that suggest emotional connections. I can’t help but assume that House Swifts may experience more distinct emotions, such as "joy" or "sorrow." As they anxiously circled outside the scaffolding, I, too, as an observer, felt their pain in a real and palpable way.

Ever since that time, whenever I hear the needle-like calls of House Swifts in the city, I open eBird and look up, trying to count their numbers—even though tracking the flocks as they dart through the sky is a difficult task. While my initial motivation conflicts with science and is driven by irrational emotions, I still feel compelled to record the presence of every House Swift. They abandon their vesper flights to incubate and raise their young. Raising chicks may be the only time in their lives when they leave the high altitudes for an extended period and stay closer to the ground. The news will eventually fade, but after experiencing the pain of being left behind, I don’t want to forget them.

Above the beams of my school's activity center, House Swifts also nest in groups. Beneath their cave-like nests, the area is covered in droppings, and occasionally, a dead chick can be found among them, perhaps having fallen from the nest. However, for the most part, there is a peaceful coexistence between the school and the swifts.

Above the beams of my school's activity center, House Swifts also nest in groups. Beneath their cave-like nests, the area is covered in droppings.

The sports day proceeded as planned in early winter. With so many high school students, it was already dusk by the time all the events concluded. Students gathered on the track for group photos, yet the hundreds of people present didn’t disrupt the swifts' vesper flights. The birds soared upward, their sharp calls echoing downward. We watch the sky every day, but no one lingers in it as long as the birds do. Gazing into the dim sky felt like looking into the deep sea from shore—evoking the sense that, if you fell into it, you might plunge into an endless abyss.

I rubbed my sore muscles, thinking that even if I had placed in the sports day competition, my body still felt clumsy compared to the swifts. Gazing at the blurred black dots high in the sky, I silently wished I could fly as high and gracefully as they did. A solitary swift quickly rejoined the flock. My eyes locked onto its dark, glossy gaze, and for a moment, it felt as though I were diving into the evening sky with the swifts, soaring with their blade-like flight.

A solitary swift quickly rejoined the flock. My eyes locked onto its dark, glossy gaze, and for a moment, it felt as though I were diving into the evening sky with the swifts, soaring with their blade-like flight.

Author Profile Lin Yu-En

Born in 2005 in Taitung, Lin Yu-En has a deep passion for birds, especially those seen from the front. A winner of multiple literary awards, she is dedicated to learning everything about them. Her accolades include the Taitung Girls' Senior High School Literature Award (2021), Houshan Literature Award (2021), and two consecutive National High School Literature Awards from the Wu-Ling Culture and Education Foundation (2022, 2023), as well as the TSMC Youth Literature Award (2023).

For more works by the author, please visit https://linktr.ee/DiGua.Su.

This piece is republished from the official website of the Taiwan Wildlife Conservation Association’s Conservation Literature | Children of the Island | Summer Story: 'Blade-like Flight' with permission granted by the author.

中

中