That day, a teammate fell ill, leaving the senior in charge of survey project¹ to shoulder the weight of two, taking me and another senior to OuCuo Beach in Kinmen. The sky hung in a bright, silvery gray, and the tide, thick and heavy, clung to the shore in slow, deliberate pulls. Our hiking boots cradled our weak ankles, leaving three sunken trails in the soft, golden sands.

Looking back at my footprints, I felt my body still too clumsy, unable to move as freely as the distant White-faced Plovers (Charadrius dealbatus), wandering with ease across the dream-like golden sands.

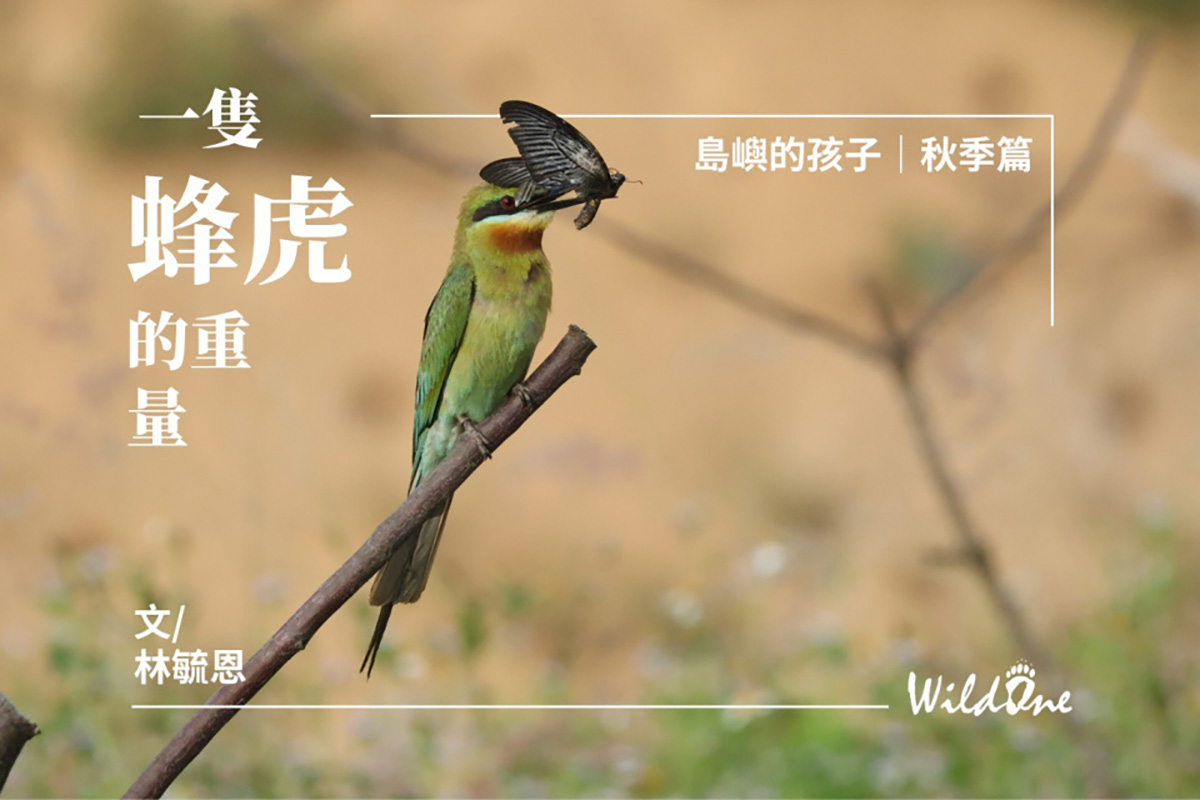

After walking about a kilometer, we ascended a steep dune, where the sharp leaves of Spinifex littoreus pierced through my pants, one by one, creating a tight, stinging sensation around my calves. Sliding down the loose sand to the other side, I finally saw our survey site—an endless expanse of rolling dunes. Yellow evening primrose blossoms stretched from the sand, and the ground was veined with a delicate network of unknown vines. Beneath the dunes lay hundreds of burrows belonging to Blue-tailed Bee-eaters (Merops philippinus).

Beneath the dunes lay hundreds of burrows of Blue-tailed Bee-eaters (Merops philippinus).

The air was thick with heat and humidity as sunshine and heavy rain alternated in waves. When the rain fell, the three of us huddled under the umbrella, pulling our bodies and equipment close. Once the downpour passed, we resumed our search for signs left by the bee-eaters. With their short, delicate feet, the bee-eaters created narrow mounds of soil along the tunnels leading to their nests. These subtle mounds guided us to burrows where the birds might be coming and going. Silently, we inserted a wooden rod with a camera lens deep into the dark, unfathomable tunnel, watching as the monitor revealed its end. Occasionally, it showed eggs the size of knuckles and glimpses of adult bee-eaters, their backs turned to the lens.

The senior explained that this is known as the burrow-calculating method: by doubling the number of confirmed breeding burrows, we can estimate the Blue-tailed Bee-eater population for the summer. I had never seen so many bee-eaters before. Although records show that the number of Blue-tailed Bee-eaters breeding in Kinmen has been declining each year, it still felt as though there were countless birds—so many that it seemed they could never disappear.

The seniors conducted a survey of the Blue-tailed Bee-eater burrows.

After the survey had been underway for a while, I followed the senior’s instructions and walked up the sand dune ridge alone, scanning the seaward side for any scattered nests.

On the other side of the sand dune ridge were more mounds of sand, stacked and diminishing in an endless, repetitive pattern. From this height, I could still look down and see my teammates, now distant. As I moved toward the seaward side, the only sound left in the wind was the faint call of seagulls. Surrounded by this, it felt as though I were floating above time itself.

When the rain came, the three of us huddled under the umbrella, gathering in our bodies and equipment. When the rain passed, we began searching for traces left by the bee-eaters.

The plants on this side were even more lush, forcing me to walk in a winding, zigzagging path, exerting effort with each step. I had handed my phone, used for recording data, to the senior before we arrived. Without it, I lost the chance for distraction, and my awareness of the surroundings sharpened. Each step made the next feel heavier. Yet resting in the scorching morning only allowed fatigue to catch up, so to push beyond exhaustion, I had no choice but to keep walking—focusing my senses forward, embracing all the messages the wilderness had to offer.

When raising their chicks, the bee-eaters constantly shuttle between sunlight and darkness. Beneath the branches near their burrows lies a layer of pellets—regurgitated by the bee-eaters—scattered around. Rub them between your fingers, and you’ll find they’re filled with the indigestible remains of insects. Do the bee-eaters, too, feel exhausted from their relentless efforts to hunt and feed their young?

The bee-eaters’ pellets are filled with the indigestible remains of insects.

A few days ago, we encountered a flightless Blue-tailed Bee-eater at another survey site. The heavy rain had just stopped, and the Asian koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus) was calling loudly while a Rat Snake (Ptyas mucosa) slithered away. We parted the damp grasses, and most of the bee-eaters, sensing danger, took flight from their perches, leaving only this one struggling in the moist sunlight, fluttering desperately, trying to escape the sticky air. The sight of its exhausted effort seemed almost to stain the otherwise barren, one-toned landscape with the hue of its feathers.

The senior caught the bee-eater, and we took the opportunity to examine its unique syndactylous foot up close. With the senior's permission, I gently cradled the weak bee-eater, and it felt incredibly light in my hands.

After taking the bee-eater to the local rescue organization2, the senior explained its origin to the staff. Curiously, I asked what was inside the plastic storage boxes stacked in the facility. As the staff gently settled the exhausted bee-eater, they told us that each box contained a Burmese python (Python bivittatus). Handwritten details about each individual were marked on the boxes, and through the ventilation slits, I could faintly see the snakes' beautiful and distinctive patterns. The patients at the rescue center ranged from the tiny, easily held Blue-tailed Bee-eater to the plump, over three-meter-long Burmese pythons. Under the professional care of the rescue team, all these creatures were given a glimmer of hope for a return to the wild.

We thanked the staff at the rescue center before returning to the wilderness to continue our survey.

We encountered a flightless Blue-tailed Bee-eater at another survey site.

The wind gradually grew stronger, and the calls of the Blue-tailed Bee-eaters were soft and bright, speaking freely to their companions in a language I couldn't understand.

After surveying most of the dunes, the almost-eternal sound of the tide grew clearer, with the wind now carrying sharp, throaty syllables. Following the sound, I climbed to the top of a dune and finally found the source—a group of about a hundred Little Terns (Sternula albifrons), mixed with a dozen Crested Terns (Thalasseus bergii), with the sea stretching out behind them.

By the time the breeding season ends, the bee-eaters and the terns will have to cross that same sea, each heading to their own destination, right?

People place great trust in migratory birds, and when these birds depart, they offer them a blessing of 'safe migration,' believing that with patience, the birds will always return to the wet fields, cracked branches, and park lawns. Even though most birds lack leg rings and cannot be identified as the same ones that left, the similarity in appearance within a species still brings a sense of reassurance, as if it were an eternal promise, unchanging since time immemorial.

When the breeding season ends, the adult Blue-tailed Bee-eaters will begin a new journey.

I wonder how that bee-eater is doing now?

For the public, escorting an animal to a rescue center fulfills a sense of responsibility. But for the staff at the center, the work goes far beyond that—assessing, treating, caring for, releasing back into the wild, and following up. They face the constant possibility of the same animal being injured again or even passing away at any moment. Whether the animal is released into the wild or dies, they remain steadfast in their duties, day after day, repeatedly saying goodbye to the creatures they care for.

Whether it's the WildOne Nonprofit Wildlife Hospital, the Pingtung Rescue Center of National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, the Wildlife Rescue and Research Center, the Kinmen Wildlife Rehabilitation and Conservation Association, the Taichung Wildlife Conservation Association, the Taipei Zoo, or various local bird associations, all are dedicated to safeguarding the lives of wild animals. No one is more eager than they are to see the sparkle of an animal's eyes once again in the wild.

Summer would come to an end, the migrant birds would depart, and the winter migrant birds would travel beneath the moon and stars to reach this place. In this very moment, I finally feel the weight of a bee-eater crossing the endless ocean to reach the island to breed. Before leaving the dunes and returning to my seniors, I take one last glance at the sea, silently wishing that the bee-eater can take flight and catch up with its companions on their migration journey.

1: The project is a collaborative effort between Kinmen National Park and the Wildlife Research Laboratory of the School of Forestry and Resource Conservation at National Taiwan University. Its goal is to monitor the long-term breeding status of the Blue-tailed Bee-eater in Kinmen.

2: Kinmen Wildlife Rehabilitation and Conservation Association.

Author Profile Lin Yu-En

Born in 2005 in Taitung, Lin Yu-En has a deep passion for birds, especially those seen from the front. A winner of multiple literary awards, she is dedicated to learning everything about them. Her accolades include the Taitung Girls' Senior High School Literature Award (2021), Houshan Literature Award (2021), and two consecutive National High School Literature Awards from the Wu-Ling Culture and Education Foundation (2022, 2023), as well as the TSMC Youth Literature Award (2023). To explore more works by the author, click https://linktr.ee/DiGua.Su。

This piece is republished from the official website of the Taiwan Wildlife Conservation Association and features the article 'Conservation Literature | Children of the Island | Autumn Story: The Weight of a Bee-eater, with permission granted by the author.

中

中