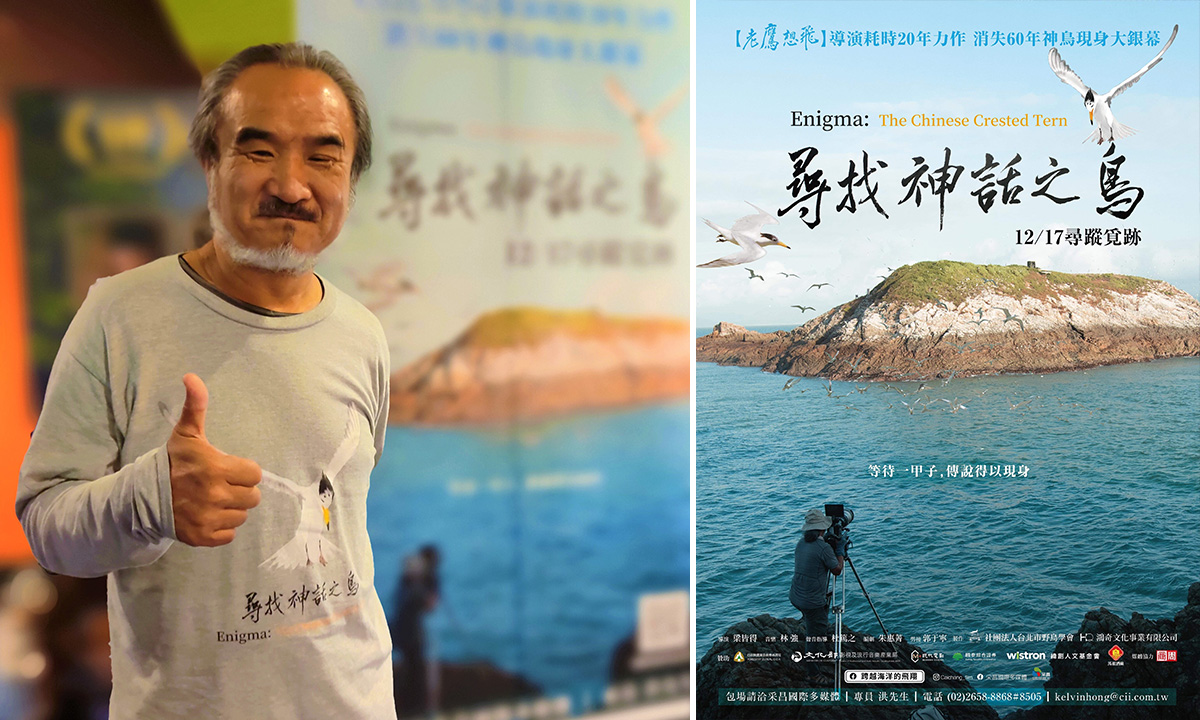

With a crown of black feathers and an orange beak with a black ink spot on the end, the light gray and white feathers of the tern has rarely been spotted by humans since it was named in 1861. So, is it really just a myth or does it actually exist? The documentary, Enigma: The Chinese Crested Tern, will unveil its story.

In 2000, because of a malfunctioning film dimmer, the director of the documentary, Liang Chieh-Te, accidentally spotted a Thalasseus bernsteini on the film, a bird that was thought to be extinct. Director Liang Chieh-Te stated that at the time they traveled to Matsu to film footage of the greater crested tern. After filming was completed and while he was inspecting the film, he found a few birds that did not look like the greater crested tern in a few of the frames with issues. The birds had white feathers on their back and their beaks were orange, with the one-third of the tip being black. After searching all the domestic and foreign bird guides, he found that these birds were Thalasseus bernsteini, which had not been seen in more than 60 years.

The news was confirmed by Liu Xiao-Ru, a researcher in the Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, after verification with international bird experts. This created a shockwave through the academic world of ornithology and excited many bird societies and enthusiasts, who all traveled to Matsu to catch a glimpse of the black and orange beak. Because of its scarce population and mysterious whereabouts, it has been named the mythical bird.

This event also facilitated ecological partnerships between Taiwan, Korea, and China. The Tiejen Island of Matsu and Tiedun Island of Zhejiang in China have been using fake birds in the hope of luring the greater crested terns and the Chinese crested terns to nest and reproduce, in order to breed the mythical bird. Furthermore, the team led by Professor Hsiao-Wei Yuan of the School of Forestry & Resource Conservation, NTU, also conducted bird banding operations, satellite tracking, and population surveys to understand the population and its habits.

The Chinese crested tern is a migratory bird spending the springs and summers in Matsu, the Chinese coast, or Korea to reproduce. In the autumn, the bird flies to the Philippines and Indonesia for the winter. The main island of Taiwan is a stopover point. Sporadic sightings have been recorded at the mouths of Bazhang River, Jishui River, Gaoping River, and Lanyang River. Therefore, Director Liang Chieh-Te traveled outside of Taiwan to film and document the birds. He started in the northern most habitats, Korea and Shandong, and made his way down through Zhejiang, Fuzhou, Matsu, Penghu, until he arrived at the southern most points, Malaysia and the Philippines, in search of the mythical bird.

Of course, he did not find the mythical bird on every trip because the Chinese crested terns are too few in number and they are difficult to track. In addition, they prefer nesting on uninhabited islands. So, the film crew had to hire boats to reach these locations and the weather did not permit going out to sea every day. An example Director Liang Chieh-Te gave was in the breeding season of 2002, he stayed for more than a month on Xiju Island, Matsu. They were only able to go out to sea to shoot the documentary for only a few days. One time, they left the harbor under heavy fog and because the boat did not have a compass the journey, which should have taken 20 minutes, took more than an hour.

Furthermore, the documentary originally focused on a Chinese crested tern called “Ma Niu.” Director Liang Chieh-Te explained that Ma Niu was a young Chinese crested tern banded by the research team led by Professor Yuan Hsiao-Wei in 2015. “Ma Niu” was found to return to Matsu every year and is able to reproduce in the third year. Therefore, the original plan was to use its story to introduce the habits of and dangers faced by the Chinese crested tern. However, in 2018, Typhoon Maria swept across Matsu and destroyed the nests. With the addition of difficult shooting conditions on the island and limited material, the film changed its narrative method to letting the director provide first person narration to tell the story of the search for the mythical bird.

Besides typhoons, the film also pointed out the biggest threat to the survival of Thalasseus bernsteini is the depletion of ocean resources and garbage in the oceans. In 2008, a Chinese crested tern was found with a straw stuck in its mouth. The “straw incident” made it to the front page of the media and inspired the Wild Bird Society of Taipei to actively invest in conservation efforts for the Thalasseus bernsteini.

From the audience’s perspective, the most touching part of the film is how the legacy of Director Liang’s family and academic legacy are woven into the narrative. There was an image in the film depicting the director’s one year old daughter accompanying her parents to the beaches of Matsu. Nearly 20 years later, his daughter is now in university and will help her father with sound recordings during the winter and summer vacations. In academia, Professor Yuan Hsiao-Wei inherited the research on Thalasseus bernsteini from Professor Wang Xiao-Ru. Now, she has passed on the work to her student, Postdoctoral Researcher Hong Chong-Hang of the Department of Forestry, NTU.

Over the last 20 years, the number of Thalasseus bernsteini increased from 8 to around 100. However, it is still a critically endangered species and the environmental risk still exists. Do humans also face the same environment filled with danger? The documentary, Enigma: The Chinese Crested Tern, invites you to view the film in the theater and ponder the relationship between humans, nature, and other species.

Podcast on Demand

中

中